| FACTS & REMEMBRANCES | HIS PICTURES Page1 Page2 | HIS WRITINGS Page1 Page2 |

FAMILY STORIES

ALLIGATOR WRESTLING

Tropical Hobbyland, NW 27th Avenue and 15th Street, Miami, 1946.

I always wanted the old man to stop but he never would. He didn't go for things like that, roadside attractions. He thought they were a gyp, clip joints as he liked to call things like that.

But I just knew they were full of wonder, exotic, strange wonderments. But I was six years old and the old man was 38 and he was driving. It was his car and he'd probably long-since lost any sense of wonder, at least in things like that.

Except he did stop there once, he must have. Or maybe somebody else was driving I don't remember. Visitors, mostly relatives, were coming down to Florida all the time and they wanted to see things. Orange trees, the flamingoes at Hialeah, the ocean of course, the fancy hotels over on the beach.

And one time somebody wanted to see Tropical Hobbyland, probably to see the Indians wrestle the alligators. That was the village's big draw. The monkeys and parrots were ok, the palm trees and flowers, the Indian women in their parrot-colored cottons weaving baskets, but the real live Indians wrestling those real live alligators was what they wanted to see.

Me too. Maybe it was Aunt Sue and Uncle Bernie who prompted the trip to Tropical Hobbyland, I don't remember. I really don't remember them visiting, but I was pretty little then, maybe four or five, before I was six and starting school. But it seems like it was them we went on the glass-bottom boat ride with out in the bay.

That was disappointing to say the least, and not just to me 'cause you really couldn't see much, an occasional fish swimming under that silly little glass window under the floor, some coral rock and seaweed, and that was about it.

I could tell the grownups were disappointed too, it was a waste. But whoever was on the trip to Tropical Hobbyland seemed like they got their money's worth. Something they'd never seen before, something they could tell the folks back home about.

One of the Seminole men would cross the sand in the walled-off pit and wade into the dingy concrete pond with a dozen or so alligators and drag one out onto the sand. Circling the sluggish animal, waiting for an opening, he'd close in quick, taking care to avoid that punishing, whiplash tail and that ugly snout crammed with huge, ugly teeth. The creature was awake now, and annoyed.

But before you knew it the man had mounted the gator's back like a jockey, leaning over it almost face to face, grabbing that snout with both hands, holding it closed, an announcer explaining that while the creature's bite packed a thousand pounds of force, the muscles used to open its jaws were relatively weak.

It was already great theater, but the show wasn't over. Holding on for dear life the Indian would wrestle the critter onto its back, holding its jaws closed with one hand he'd begin rhythmically stroking the reptile's belly. Next thing you knew the beast was sound asleep and the wrestler was up, waving to the crowd, acknowledging the applause.

Fifteen minutes of real theater and I guess the crowd along that waist-high wall got its money's worth because people were clapping, throwing coins out onto the sand, the wrestler scooping them up, joined by a couple other men, wrestlers all scarred one way or another by the beasts, dumping the silver into a bucket.

I was just a kid but I remember being embarrassed for the tourists, appalled at how cheap they were, how small, for the show they got, Ashamed. Mortified.

Embarrassed for the Indians, grown men, some as dark as negroes, forced to put on a show for spoiled white people, groveling, for all intents and purposes, for change from the fat white tourists, chump change tossed there on the sand.

I suppose Tropical Hobbyland paid those men something too. It was the park's feature attraction, its biggest draw. But still.

GRANDMA STONE'S SWITCH

Grandma Stone lived next door when I was a kid in Miami. She wasn't really my grandmother, except that she was everybody's grandmother. And she didn't really live next door, except part time.

Grandma was shuttled back and forth among her children for a few months at a time, when it was time for one of them to take his or her turn to "take mom." Two sisters and their families in Miami, one of her sons and his family in Louisville.

Grandma must have been somewhere in her 70s when I knew her right after WW II, and she ruled the roost wherever she was. She was everybody's grandma and she let everybody know it.

She was Irish and Catholic and she let everybody know that too. She believed in law and order --- her law and her order --- and never flinched from declaring it, and enforcing it, among us kids.

Her daughter Ann and Ann's husband Smitty lived next door with their two kids, Charles, a year older than me, Mary Ann a year younger. Ann's sister Mary Catherine and her husband lived across town and their brother Danny lived in Louisville.

Grandma was stout, as they used to say. She worked hard all her life, raising her kids on the wages of a washerwoman, and whatever the church could spare. Her husband had trouble holding jobs, and went without a good deal of the time people said.

She'd come over from the old country when she was 8 and went to work keeping the parish cathedral and rectory clean. When her church chores were finished she went about scrubbing the floors of downtown office buildings down on her hands and knees, mopping when she was lucky. Mopping the same city hall and police station floors her son Danny would walk when he became a cop.

I suppose Grandma was "retired" when I knew her, but that only meant she wasn't chasing a paycheck anymore. I don't know what things were like around Mary Cat's house --- I don't remember ever being there --- but next door to us Grandma had a full-time job. Ann sat around the house listening to the radio and drinking beer most of the time, and Grandma did everything else.

Everything else included riding herd on us three kids and keeping an eye on my sister who was a little older. Grandma had to badger Ann into driving her to the grocery so she could do the shopping and then do the cooking, the cleaning and the rest of the housekeeping. Ann and Mary Cat had the habit of "good naturedly" complaining when it was their turn to "take mom" but it's hard to see how things could have managed next door without her; she was putting in six months at a time over there by then.

Grandma spoke with a heavy brogue, which lent her directives a kind of exotic flavor, and vested them with a not-to-be-denied emphasis and authority. The directives were directed mostly to us kids and we all were familiar with her no-nonsense tone of voice and certain favorite expressions, commands which let you know right away Grandma was on the case.

"Suren't it's the back of me hand you'll be getting!" and, "Mary Ann, you better ask the Lord to direct you!" are my favorites and we heard them often, especially slow, day-dreaming Mary Ann. And, depending on her tone, they usually meant you better straighten up in a hurry.

But Grandma was basically a jolly person. She loved to laugh and laughed often, she liked to tease and joke, ready to see the humor in everyday life, unless you crossed her. She believed in the "big stick" theory of child rearing, and her stick was usually a switch she'd come up with at the drop of hat.

In south Florida we were bare-legged and outdoors most of the time after school and in the summers, and she could fetch you a whack across the back of those bare legs before you knew it, especially if you talked back. She could move pretty fast for a big old woman, a lesson we learned quickly. When she was particularly exasperated, she liked to announce that soon she'd be "After getting me shillelagh," but I don't believe she actually had one.

Grandma had Faith, with a capital F, and certain little homilies she firmly believed in. "Aye, go on, a little bit of dirt's good for ya," by way of encouraging us to go ahead and eat whatever piece of food we'd dropped. She believed in mercurochrome and merthiolate for our constant cuts and scrapes; iodine for the serious ones.

It was iodine that got her "in Dutch," as they used to say, once with Ann. Grandma had heard somewhere that a drop of iodine in the daily glass of orange juice would help build iron in kids' blood. So with her personal philosophy of "If a little bit's good, a whole lot's better," soon she started adding several drops of the stuff to our juice.

A few weeks went by and we kids began developing a noticeable orange glow on our hands and faces and Ann started wondering what the hell was going on. Charles blabbed about the old lady adding four or five drops of iodine to our juice every day by that time and Ann hit ceiling, convinced her mother was trying poison us.

But that was Grandma. Ann soon calmed down and went back to letting Grandma run everything, sans iodine. And running everything turned out to include running my sister's would-be beau out of the neighborhood one Saturday afternoon.

My sister Shirley was five years older than me and a senior in one of the public high schools, already shaky ground as far as Grandma was concerned, and she never approved of how short the shorts were my sister wore as part of her majorette uniform. When one of the boys in Shirley's class drove up in our yard to pick her up for a date, Grandma put her foot down.

She trundled out her front door, flying across the yard and assailed the poor lad through the car window before he could even get the car door open, demanding to know whether he was Irish and Catholic. Pretty soon the boy was so unnerved he never even got out of the car, backing out into the street and fleeing the scene before my sister could even get out of the house.

Needless to say, my sister was thoroughly mortified, as you can only be at that age, but she got over it soon enough, because, after all, that was Grandma. And that was a good thing because we moved away the following February and we never saw Grandma again.

Our family moved to Louisville where my parents were from and we heard later Grandma had gone back to Ireland and died. Ann and Smitty were from Louisville also, and they moved back with their kids a few years after we did. They located at the far end of the county and Charles and I exchanged a couple of perfunctory visits, but we never hit it off and we didn't pursue it.

The families pretty much fell out of touch, exchanging Christmas cards and such, visiting once or twice a year, until Mary Ann drove head-on into a fatal collision out on Dixie Highway in Valley Station. Poor dreamy Mary Ann, a little slow, a little naïve, always seeming to get the short end. My sister was working in an insurance office when the police report came in, knocking her off her feet.

At the funeral Ann was skin and bones, a skeleton, living pretty much on nothing but beer by this time, and we knew deep down, we'd be going to her funeral before long. Her brother Danny, the cop, and his wife were there, some relatives we barely knew, several strangers we didn't.

At the funeral we learned what had happened to Grandma. She had gone back to Ireland by herself, to her long-lost family who'd never left, home to somewhere near Cork. Irish and Catholic to the end, she'd bent and kissed the Blarney Stone, in the proper fashion by all accounts, and died about three months later they said. She was 83.

AUNT SUE SHOOTS A STUFFED FOX

My aunt who shot the stuffed fox lived most of her eighty-odd years in the Germantown neighborhood in Louisville. She shot it with her personal sidearm, a .32 caliber nickel-plated Colt revolver with pearl handles, which she carried in her purse.

She was my great aunt, my mother's aunt, born Lucille Honaker in the West End at the tail end of the 19th century. She married Bernard Gauspohl and they had one child, Elmer, who soon jettisoned that yappy name for Bob, and who was unlike them in every way imaginable.

Lucille went by "Sue" and that's the way everybody knew her. She liked beer and pinochle and the Friday night fights on TV, and a series of yippy little Pekinese that barked incessantly and couldn't have been more irritating if they tried, but I always believed they did. She drove her own car, which she referred to as her machine, and every so often couldn't remember where she'd parked it.

Her husband, Bernie, was the service department manager at Louisville Motors, the city's original and largest Ford dealer, downtown. Bernie was a short, wiry man, quiet, who loved to fish. He liked catching crappie and bream, cleaning them and dredging them in cornmeal and eating them, frying them up in a big black cast iron skillet, swimming in Crisco.

And he was the originator of course, of the "Uncle Bernie Plate," from which every morsel, every sliver of a morsel, had been eaten and sopped up after. The joke around the table was always that that plate didn't need to be washed, it was already clean, as spotless as when it came out of the cabinet, and Uncle Bernie would beam.

Sometimes us kids would get real tired of hearing about Uncle Bernie Plates when we were so often urged to accomplish them, sometimes, "if we knew what was good for us," because we had to eat at least one helping of everything prepared, like it or not.

But we could never blame Uncle Bernie, a singularly kind and patient man, not generally the norm in those days, who taught my sister to drive as soon as she was old enough after we moved to Kentucky, when nobody else could or would.

Bernie's son, "Bob" had much the same kind of generosity. Not offhand, but measured, deliberate and specific. He might as well have been a Jew in WW II Louisville, outsider, brainy and working class, with plain parents and plain prospects.

But the US Navy claimed him, commissioning him an officer and commandeering the next six years of his life.

Bob attended the University of Louisville, at the time a small city-owned and administered college of modest distinctions in the fields of medicine and dental practice, law and psychology, the "cultural," professional pursuits, and the reputation for being a little snooty and better than you.

And certainly better than the clumsy land-grant colleges in the state system, mostly dedicated but ill-prepared for turning out school teachers for a poor, generally backward state. Kentucky.

At U of L, Bob hobnobbed with several members of the Pendennis Club, a traditional, paternalistic social club for white males of some means, because he was smart and sophisticated and because he was an excellent bridge player. Good enough, and a good enough partner, always welcome at one of the tables where good-sport money often changed hands.

Bob couldn't have afforded membership in the Pendennis Club and a man of his background, his class, wouldn't have been welcome there except for the manners and "class," the social graces, he had cultivated.

They stood him in good stead for the rest of his life, and immediately at Cornell, in the Ivy League, where the Navy sent him to finish off his education after plucking him out of U of L.

Bob became a doctor, specializing in psychiatry, a couple of years after the conclusion of WW II and was sent to Japan for two years as part of the U.S. occupation force. And he owed the Navy four more years of duty as repayment for his Cornell degrees.

After a subsequent yearlong tour stateside, he requested a transfer back to Japan where he spent the next four years and married Kanuoa. He brought her back to the states and opened a psychiatric clinic in Los Angeles, where they had two children, a girl and a boy.

But Kanuoa was never at home in LA, and after a few years she took the children and moved back to Japan. Bob followed shortly in an effort to salvage the marriage, even selling his share of the practice to his partner, but the reconciliation failed and he returned to the states.

I met up with Bob years later in LA while serving out my time in the Army. I'd been across the state in the Mojave on a three-week peacetime maneuver involving 120,000 U.S. servicemen. 34 of them died, half in their sleeping bags on the hard desert floor, run over by tanks in the night.

I called Bob in the middle of the day and he met me in a Santa Monica bar called the Brass Rail, across the street from the ocean pier. He was still wearing the trim Boston Blackie mustache he wore on his last visit home to Louisville.

On that visit he kept company with Helen Thornton, a young woman bordering on voluptuous, so sexy in her summer shorts and blouse. I was 15 and it was the first time I'd been that up-close in-person to a grown woman that sexy, and that self-assured about it, so sophisticated. It was hard not to stare, not to marvel.

Bob bought my sister a top-of-the-line tennis racket for her birthday, celebrated in Aunt Sue's sun room in the St. Matthews tract house down the street from my parent's house, which she'd bought the year before and where a couple of weeks earlier she and I had watched Sugar Ray Robinson polish off Rocky Graziano on her new TV, and I was allowed a single can of Pabst Blue Ribbon.

It was in that house that Aunt Sue had happened on Bob and Helen smoking reefer late one night, still a terrible thing not that long after the showbiz scandals of "potheads" Gene Krupa and Robert Mitchum. Scandalized herself, she nevertheless told my parents and grandparents and probably a few other relatives about it. Bob was amused.

Six months after our Santa Monica meeting Bob was dead, by his own hand and a small-caliber automatic, in his three-bedroom ranch house in an LA suburb. Nobody ever knew why. Aunt Sue and Uncle Bernie took it hard.

Neither of them understood or knew anything about Bob, really, or his Japanese wife and children. But it didn't matter. He was theirs and always would be, and they had tried. Especially Aunt Sue. They'd made two trips out to California when Kanuoa and the kids were still there, when travel wasn't that easy or facile for two middle-aged adults rooted in Louisville.

But they didn't take. Never had a chance really, people from different worlds. Bob too, actually.

I took it kind of hard too, though I didn't really know Bob either. But I always felt a little guilty that I'd chased my cousin down clear across the country, my cousin, a stranger, to tell him my own puny personal problems, in a bar, when his business had been to listen to hundreds of people's problems through the years. Everybody else's problems.

They tried. Aunt Sue never tired of telling the story years later about the time when Bob was a skinny, bookish 12-year-old and he'd backed down the bum who was threatening to come onto their porch where his mother stood defenseless, with a 12-guage, knowing all along the gun wasn't loaded. It was a delicious story and she loved telling it.

Uncle Bernie had tried to teach Bob's five-year-old to fish, but the boy wasn't interested, and that didn't take either.

Aunt Sue went on with her canasta and pinochle and Friday night fights on tv and Uncle Bernie kept on fishing and frying them up. Anytime somebody in the family was in the market for a good clean used car, Bernie would keep his eye out for a likely prospect and have the mechanics at the garage give it a good going go over.

Aunt Sue would meet my mother and grandmother downtown on Saturdays to "whip Fourth Street," which was how they referred to their weekly shopping expeditions. From Broadway to Market Street, up one side of Fourth and down the other for eight or nine blocks, they went through all the stores shopping for clothes and notions and whatever dry goods they might need.

There were always holidays and birthdays to be prepared for. Before the malls took over, downtown, mostly Fourth Street, was where Louisville ladies did their shopping, in the big department stores and the smaller specialty ones, several of which would move on to the suburbs later and call themselves boutiques.

They'd make a day of it, treating themselves to a nice lunch at one of their favorite restaurants before boarding their buses back to their respective neighborhoods, carrying various bags and boxes home on the bus, in time to fix supper.

But downtown died in the late 50s, a victim of progress. I-65 was routed right through the middle of the city, destroying whole sections throughout the county, especially in the city, for blocks all around on both sides of the biggest road the state had ever seen. Whole neighborhoods were uprooted, neighborhoods that defined Louisville and had passed from generation to generation for better than 200 years, withstanding two world wars and an epic flood, disappeared.

Earlier in the decade Mayor Charles Farnsley had been instrumental in coaxing General Electric's construction of what became the state's largest factory, on the edge of town, and enlisting its indispensable support of the city's world-class orchestra, beginning to thrive under the direction of conductor Robert Whitney. Both developments put Louisville on the map in the post-war boom years.

Farnsley warned that sending the highway through the heart of the city would kill it, and it did. It's debatable whether it has ever recovered. The city became less friendly, a little rambunctious, rowdy, occasionally even threatening. It was time for the ladies to move on.

Progress saw the wholesale development of the boundless suburbs which soon ringed the city. People moved out there and the stores and malls followed immediately.

For a time my mother and grandmother would take their places in Aunt Sue's Ford and do their shopping in the malls. But something was missing, that collegial feeling of shopping together.

The malls, with their tacky outlets laden with junky discount goods, mixed in with the traditional, familiar, reliable stores, seemed to demand an efficiency equal to their own, impersonal and disorienting. Shopping wasn't so much fun anymore.

So they quit and did their shopping in the evenings. They became a little more distant, saw a little less of each other, meetings more planned, arranged, more often at night and for special occasions, birthdays, holidays.

I went to college, the army, got married, and saw a lot less of the ladies, particularly Aunt Sue. She stuck even closer to Germantown, playing cards and drinking beer, over-tipping the bandleader on bingo night if he'd play "Sweet Sue" or some variation.

She and sometimes Bernie would show up for the occasional family get-together, friendly, sentimental. Sometimes she'd get a little drunk as they used to say, but not Bernie. With Uncle Bernie it was harder to tell.

They bought a little bungalow up on the river northeast of the city in Harmony Village. The village consisted of a half-dozen more or less identical concrete block cottages on 100-ft lots facing the river, running down to the water's edge, in a patch surrounded by small family farms, and were called camps, summer places generally occupied from late spring to early autumn.

To get there you took the four lanes of US 42 toward Cincinnati, turning off after 20 miles at Prospect, onto the two lanes of Rose Island Road for another five miles under the canopy of old oaks and maples and the cottonwoods down by the river.

The "camps" were one bedroom, affairs, a living room, full bath, an ample kitchen and a screened-in porch stretched across the width of the cottage, overlooking the river through the trees.

The buildings had large attics for storing summer's accommodations through winter, because the river flooded every year, the water usually stopping at the foot of the porch, but occasionally lapping up to the first floor.

The porches were 10-ft deep, reached from ground level by a dozen heavy wooden steps anchored in concrete, and floored with linoleum.

The area opened to the kitchen, serving as a dining room, a place to play cards, listen to the record player and to just relax, including afternoon naps.

A large patio area was leveled off 10-15 yards down the bank, stabilized by 15 square feet of poured concrete with a heavy wooden table, five-feet in circumference and heavily weatherproofed, set on top. The patio and table caught the first items brought down from the attic in the spring to "air-out."

Sue and Bernie's next-door neighbor, Sam Slorenco, brought his attic stores down to his patio one morning in the middle of April in the late 50s and set some of it on the table, including his prized stuffed fox. Sam's red fox was a beauty, full-size, expertly caught in a foxy pose and mounted on a beautiful walnut plaque.

Squirrels, raccoons, opossum, groundhogs and various other woodsy wildlife, including the occasional fox, were constant visitors in the village, mostly at night, sometimes to the point of becoming pests. So when Aunt Sue drilled Sam's stuffed fox it was a natural mistake.

She'd spied the ornament on her way through Sam's yard to my grandparent's place at the end of the row, and went back to get her pistol. Sam was inside rummaging through more stuff when he heard the shots. He hurried down to the patio where Aunt Sue was bent over studying the animal she'd blasted clear off the table.

Aunt Sue was shaken, Sam Slorenco bewildered. It took them several minutes to realize what had happened. The sheer incongruity of it, the seeming impossibility of something like that actually happening, was hard to take in. Chief Doyle came over right away, his own pistol in hand, and things gradually cleared up.

Sam was speechless and Aunt Sue was breathing hard, babbling incoherently. She was still holding her gun till Police Chief Doyle took it, reflexively disarming any shooter on the scene. He sized up the situation pretty quickly, and saw the humor in it right away.

Before long they all were laughing, even Sam and even the hugely mortified Sue, repeating the sequence of what must have happened, over and over, amid wild shrieks of laughter. Sam was fingering the two bullet holes in the critter, a steady Aunt Sue having brought both rounds home.

After awhile Sam announced the nature and depth of the lawsuit he was going to bring, after all he was a lawyer for crying out loud, setting them all to laughing hysterically again. Aunt Sue kept apologizing, sputtering and trying to explain, vowing to have the poor fox fixed, bringing on more peals of laughter. It was funny, so funny and they just couldn't stop.

All in all though, it was probably a good thing that it was a fine, crisp spring morning and everybody was in a happy frame of mind. And nobody had had any liquor yet.

BACK TO TOP

ESCAPADES

STUDY HALL TRICKSTERJudy Neil sat cater-corner from me in sixth period study hall when we were seniors. Study halls were 50 minutes long, just like the rest of the class periods. We sat at smooth, bare, blond wooden tables, twice as long as they were wide, four to a table, 30 tables in the school library.

No talking, no chewing gum, or anything else. Sleeping was permitted, head down on the arms, but studying or reading was preferred.

Study hall was presided over, ruled by, Mr. Kemp, a natty rooster pushing 60, with a booming voice and zero tolerance for outlaws. The penalty for any and all infractions was a trip to the library's entrance hall to stand up for the rest of the period, proper posture required. Those apprehended late in the period or guilty of bad comportment while serving their sentence, could expect to serve at least some time the next day. And Mr. Kemp never forgot.

That's why Judy Neil was so aggravating. She took some sort of perverse delight in provoking me into some behavior sure to catch Mr. Kemp's attention, the last thing anybody wanted. And she did it although, almost as often as not, she had to pay the price too. By the time the year was half over she'd managed to draw enough attention to our table that we became one of Mr. Kemp's regular checkpoints.

Her favorite trick was to tap my foot under the table with hers and smirk, "Are you trying to play footsie with me?" My favorite rejoinder was, "Don't flatter yourself." And like all retaliators, I was the one who got caught. Talking. She had other tricks but that was her favorite, and she was an artist with her timing, waiting till the stage was set just right so that I'd be the one caught.

But I'll have to hand it to Mr. Kemp, pretty soon he caught on to Judy Neil the trickster and she got caught a little more often. Mr. Kemp was nobody's fool for sure. He taught only one class, Aeronautics, only for seniors and there were never more than two or three boys in the class 'cause you just knew it was gonna be harder than hell --- Mr. Kemp? Aeronautics? Besides it was during first period.

I didn't even know Judy Neil. I'd seen her in the hallways of course but paid no special attention and going on four years we'd never had any classes together, never met at a party or anywhere else. Being study hall "partners" was our first real proximity.

But she was cute. About five-four, almost skinny, blue eyes and medium-brown hair, with perky little breasts accented by the crewneck sweaters she always wore. Always. A-line skirts and black flats, blue or white or pink oxford cloth shirt collars showing under those sweaters. Preppy suburban high school girl from central casting.

Judy Neil had a sharp little nose and a lively face. She was cute and lively, animated I suppose is the right word. Devilish even, you might say. Lots of personality and it's a shame I never got to really know her.

Of course we never actually got to talk in study hall. We walked out of the library into the last-bell rodeo of the first-floor hall together a couple of times, but everybody was pushing and shoving, scrambling to get out of the building, school was out and I couldn't wait either.

But we did make a date once. She asked whether I was going to the school dance that night and I allowed as how I wasn't planning on it because I didn't have a way to get there and I wasn't sure if I could get our family car, which was a joke because I could never get the family car, and the dance was at our school way out in Middletown, eight miles from the suburb where I lived. She said she'd drive and she'd pick me up in front of the drugstore at the corner of the 'burb's main intersection that evening.

The intersection bisected the town and the old drugstore was a landmark. The building was brick and had a waist-high narrow ledge about four inches wide the width of the store where my buddies and I would rest a minute sometimes during our nightly rounds of the town.

Jim Misner was keeping me company that night and I knew he was a little bit jealous because a good-looking girl was picking me up there in a few minutes. I'd been picked up there a couple of times before, but not this night 'cause Judy Neil never showed up and Jim needn't have been even a tiny bit jealous. But we both got our chance a little later, in spades.

We hung around for the better part of an hour, after all we didn't have anything better to do anyway. So we were in place about nine o'clock when this gorgeous candy-apple red '55 Chevy hardtop came off Chenoweth Lane and turned onto Shelbyville Road right in front of us, heading East, with that dumb damn Donnie Dever behind the wheel. And worst of all, gorgeous blonde Carly Sue Revell was with him.

And worse, she was practically in his lap, shifting the car up into second as they made the turn, glancing over at us for a second and then they were gone. Gorgeous Carly Sue with her gorgeous go-to-hell blonde ponytail. At least Dever had the good grace not to get rubber on the spot, but I always wondered whether it was just because he missed it.

I don't remember much else about Judy Neil. I must have tried to get back at her some way for standing me up, but I don't remember it. And it seems funny that I remember her so clearly, we never went out and I never saw her again after high school. Oddly, I remember her better than any of the other girls in school, Carly Sue or any of the half-dozen knockouts there. Or girls I actually did go out with, in school and otherwise, girls I actually liked. Seems funny after all these years.

CHATTAHOOCHEE

My father was fond of telling me every once in awhile that I was gonna wind up in Chattahoochee. Chattahoochee was the state nuthouse when I was a kid, and still is actually, I think. Located in north Florida on the Georgia line, hard by Alabama, 45 miles northwest of the state capital in Tallahassee. Called the Florida State Hospital nowadays I believe.

The Chattahoochee River starts somewhere up in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Google doesn't seem precisely sure of just where, and rolls on down past the town of Chattahoochee in Gadsden County for 400-some miles in all before ending up in Apalachicola Bay at the Gulf of Mexico.

One-hundred and fifty miles back upstream from Chattahoochee the river flows through Columbus, Georgia, forming part of the Georgia state border with Alabama. Columbus is the site of the Fort Benning military base and its airborne school. I spent a cold January there in 1963 learning how to jump out of airplanes.

Columbus is also the birthplace of Carson McCullers, maybe my all-time favorite author. I say maybe because I really couldn't pick just one single favorite among a hundred other favorites. But Ms. McCullers, nee Smith, would surely rank right up there at the top.

Born Lula Carson Smith in 1917, she acquired her musical surname when she married Reeves McCullers, an ex-soldier and aspiring writer from Alabama, in 1937. She was 20, he was 24.

Three years later Carson had dropped Lula, but hung onto her new lilting last name when Houghton Mifflin published her first novel, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, and the rest as they say is history.

I'd read the book back in high school, quite taken with its title and the sound of the author's name. It was the 50s and I was still an impressionable kid. My favorite habit was to sit in class with a textbook propped open on the desktop with a paperback novel tucked in behind it, following along with class goings-on just enough to keep out of trouble.

That was my introduction to Carson McCullers. And a lot of others. Steinbeck and Hemingway, Faulkner, Dos Passos and Dreiser, and a ton more. It was the heyday of the paperback, they were everywhere, 25-35 cents for Mickey Spillane, 50-75 for more "important" stuff such as The Grapes of Wrath or The Young Lions, just waiting there to be liberated from their revolving drugstore racks.

I kept up with Carson, securing copies of Reflections in a Golden Eye, The Ballad of the Sad Café, The Member of the Wedding, as soon as they hit the racks. Those titles. I was sure she had to be cool, even though I could barely define it in my own mind at the time. And she was.

The great John Huston filmed McCullers' second novel, Reflections in a Golden Eye, in 1967. It was not good despite the high-powered presence of Marlon Brando and Elizabeth Taylor. Huston made several very good movies, and arguably a couple of great ones, but this wasn't one of them.

It's an ugly story, set on an un-named army base in the South, perhaps nearby Fort Benning. A year later the film of The Heart is a Lonely Hunter was released and it's somewhat better, redeemed in great measure by an inspired Oscar-nominated performance by Alan Arkin.

The movie version of The Member of the Wedding, directed by Fred Zinneman, opened in 1952. Multiple Tony Award-winning actress Julie Harris reprised her Broadway role as the 12-year-old tomboy Frankie, in spite of being 27 at the time, and was even nominated for an Academy Award. Harris pulled off the same trick three years later when she was cast opposite James Dean in East of Eden when they were both supposed to be 17.

No such luck for The Ballad of the Sad Café in 1991, produced by the most unlikely team of Merchant/Ivory and directed by British actor Simon Callow. The film went off the rails immediately with the sinful miscasting of English actress Vanessa Redgrave in the lead role of a backwoods bully in classic Southern Gothic style.

Redgrave was an accomplished actress but she couldn't begin to overcome that original casting blunder, the woefully inept script or the peculiar selection of the inexperienced Cork Hubbert in the pivotal role of Cousin Lymon. Only Keith Carradine and a typecast Rod Steiger emerged relatively unscathed.

All of Carson's celebrated stories are set in the small-town South, and all depend on her artful use of language to be properly understood and appreciated. Not surprisingly, by and large Hollywood just didn't get it. More surprisingly, Hollywood seemed to get her friend Tennessee Williams, at least some of the time, but they just didn't get Carson McCullers.

Carson McCullers left Columbus when she was 17, but not for good, returning quite often through the years until her death at 50 in 1967.

My first and last visit to Columbus was a month-long stay at Fort Benning. I had dropped out of college in February, 1962, because my girlfriend thought she was pregnant and I had to get a full-time job so we could get married.

The "pregnancy" turned out to be a false alarm but I still needed a job so I could afford to re-enroll in September. But September never came. Or rather it came and went without me.

I got drafted in August since technically I no longer had my college deferment. I'd signed up for the second semester but withdrew as planned after two weeks, but I failed to realize the University of Louisville was legally obliged to notify my draft board that I was no longer a full-time student entitled to the deferment.

That board was local board 42, the same as Cassius Clay's, but you couldn't blame them, my own ignorance was at fault. Clay got married a couple years later and by then he was Muhammad Ali, heavyweight champion of the world, and had moved to Michigan, I think. He had refused to be inducted but I hadn't.

I'd met Cassius Clay, who was two years younger than me, in Columbia Gym, a dark, dank basement auditorium below an old Catholic women's college in our hometown, Louisville. He was a skinny, incredibly smartass punk who stung me silly with a lightning flurry of punches right on my nose, ending my teenage boxing "career" then and there.

My high school pal Jim hung out there for a few more months but I quit a couple weeks later, a lesson learned, faster than anything I'd ever seen, before or since. Jim and I had wandered in from our suburb in the summer of '53, for something to do and it turned out to be more than enough for me.

I tried to join the navy when I graduated from high school but was refused because I was only 17 and lacked parental permission. And, I had a criminal record as a juvenile delinquent for a bunch of penny-ante stuff. That record meant I couldn't be drafted, or so I thought. So, safe from the army and the draft, I bummed around a couple years, in and out of college.

That wasn't the way Rita M. Boyd was thinking however. Three years later that fat pig-eyed draft board bitch hustled me off for eight weeks of basic training at nearby Fort Knox, in the proverbial New York minute, August of '62, record or no record. That record was supposed to be expunged when I turned 18, but to this day I'm not sure it ever was.

And then on to Fort Sill, the army's artillery center in southwestern Oklahoma, for eight weeks of advanced individual training. It was a competitive eight weeks of mostly classroom study in celestial navigation, three-dimensional trigonometric calculations derived from astronomical observations. There was a high attrition rate and half the class flunked out.

A rumor went around that the remaining eight of us were going to be posted enmasse to Korea for 13 months, and the rumor turned out to be true. Whoa. A truly dreadful prospect. But I had already passed up one opportunity to escape, officer candidate school. OCS entailed adding a year to one's enlistment and since I was already on the hook for two years of active duty, that had zero appeal. And as luck would have it I caught another break.

The break came in the form of two E6 sergeants in swell tailored Class A uniforms and bloused boots, who were going around from base to base recruiting slick-sleeve privates for airborne training, and I jumped at the chance, so to speak.

That was the last two weeks of December, '62. I got delay-en-route orders to report to Fort Benning at midnight on January 3rd which meant I got to spend the better part of two weeks at home for Christmas, and I wasn't going to have to spend a year and a month in bleakass Korea. Hallefuckingleujah!

I caught a Greyhound to Louisville from Sill, and another one two weeks later that got me to Columbus by noon on the 3rd where it was a brisk 20 degrees. I got my gear from the bus and ran into Willie who'd come in on the bus that had just pulled in right next to mine.

Willie --- Maurice Williams --- and I lived on different floors in the same barracks at Sill, and we'd palled around some there. We decided we needed to get in out of the cold and headed for a diner down the street. But that didn't turn out too well.

We copped a couple of stools at the counter and ordered up but some lunch but the woman behind the counter wasn't having it. She kept saying, "You want that to go don'tcha?" She said it two or three times and I still didn't catch on. But Willie did. Guess he was used to it, being a man of color and all.

He stood up and said, "C'mon, let's go." I stood up but I was wondering why we would want to go back out in the cold to eat. Besides, we didn't even have anything to eat. We were out the door before it hit me. I felt like all kinds of a fool, I was so embarrassed for Willie, for being white. This was Georgia, in the brand new year of 1963. Shit.

Willie didn't seem nearly as pissed off as I was. But like I said, I guess he was used to it. Willie was from Tulsa, but I didn't even know anything about all that back then. Years later when I learned about it, I'd get all pissed off all over again. And I never will forget that ugly fat counter woman. Reminded me of Rita M. Boyd.

Willie and I got a local bus and went on out to the post and got something to eat in the PX even though it galled us plenty to report early. But it was cold. We lived on different floors again and I never really saw him again except for running by once in awhile, we were always, and I mean always running in jump school. Except for the last day when everybody was marking up the forms for where they wanted to be stationed next. Willie had requested Okinawa, and the last time I saw him he was grinning like a fish 'cause he'd gotten it.

I had requested Fort Campbell because its address was in Kentucky and it was one of the four places you could be stationed and stay on jump status. Jump status meant you had to make at least one jump every three months. It also meant getting an extra 55 dollars every month --- 110 for officers --- which was actually classified as incentive pay, but we always referred to as hazardous duty pay.

I got to Fort Campbell but it took me a year. I got another delay-in-route, courtesy of the Special Forces, in the person of another in-army recruiter who was looking for volunteers who were already jump-qualified, to join a new outfit. The second requirement was to have at least 18 months remaining on your enlistment, and I did, just barely.

The deal was billed as a special unit, a small, elite group that wouldn't be bogged down with a bunch of routine duty and boring time in the barracks. The group would be stationed at Fort Bragg in western North Carolina, also the home of the 82nd Airborne Division, the army's most-decorated unit.

SF members would wear snazzy green berets instead of regular standard-issue headgear, and would remain on jump status. Staying on jump status meant getting that extra 55 dollars a month over a base of about 80 bucks, but more importantly, it meant getting to jump out of airplanes on a regular basis, which was a lot better and more fun than anything else I ever expected from the army.

I was 20 years old and life was definitely making a big swerve toward adventure, leaving a lot of aimless, jumbled-up days in the ditch. I was an easy sale for that recruiter. If I had to spend another year and a half in the army, I might as well go first-class.

Saying goodbye to Benning and Columbus was easy. The last week of jump school consisted of making our five qualifying jumps just across the muddy Chattahoochee onto flat, plowed fields in Alabama. Three or four 'cruits on my planes had never actually landed in a plane yet. And I thought I was green.

Goodbye Columbus, and any tenuous ties I imagined with Carson McCullers, who I never even got to meet. She died four years later after being plagued by bad health most of her life, and a bad husband off and on. I was already being consumed by a paperback novel named Catch 22 , by Joseph Heller, I had picked up at the PX in Fort Sill.

I'd lie up in my top bunk reading it and hand down a few pages I'd already read and torn out, passing them down to Tohinaka in his bunk, at his insistence, 'cause I was laughing hysterically page by page and he couldn't wait to get his hands on the book, even in that raggedy, impromptu serialization of it.

Ken Tohinaka was a first-generation American Jap from Salt Lake City, and a draftee too, a dual math and philosophy major at UCLA, and immediately he was laughing as hard as I was while passing his handful of pages onto the next guy, and relentlessly demanding more pages, until there were a half-dozen guys milling around the barracks, clutching torn-out paperback pages and giggling. Catch 22 got around, and everybody had a share.

I ended up reading that book all-the-way-through ten times at last count, and I couldn't even count the paragraph and page-length bites I've called up in the last 50-some years.

I moved on to Fort Bragg and I was there when President Kennedy was shot. We'd been out in the field for a couple weeks and when we rolled into the company area the CQ came running out of the orderly room yelling, "The President's been shot! The President's been shot!" which was the most unimaginable, unbelievable thing I'd ever heard in my life.

Things were hectic around there for quite awhile. Thanksgiving and Christmas were pretty strange, but they came and went and things calmed down a little. I had already applied to the SF language school in Monterrey, California, but there was a catch. And it wasn't Catch 22. It was a catch I should have caught: that school required 54 weeks left on an enlistment and I only had 50, so I was automatically rejected.

And things got worse. A lot worse. The paperwork my application generated caused too many people to pay too much attention to my enlistment status. I was too "short" to qualify for that school because I was a US. US was a serial number prefix indicating one's enlistment status at a glance. I was a draftee, sticking out way too far in that outfit.

I was the only one in the company, a fact that had somehow escaped the attention of all the lifers up to that point, probably because I was such a good, dutiful soldier. Now that cover was blown. To smithereens. But all I had to do was re-enlist for three more years. Or four. Or even six, the options were adding up, and so were the bonuses. Ha, ha.

"We're all volunteers!" an exclamation I heard often in the next few weeks. The lifers just couldn't understand how I wasn't interested in re-upping, "finding a home in the army," as so many of them had. When it was plain the regular bonus options probably weren't going to work on me, they started trotting out some quieter schemes.

If I'd re-enlist they would boost my pay grade up a notch, maybe even two with a waiver, so I would actually have the rank my job called for, instead of them having to get a waiver for it which they had already done anyway. And, I could get a top-secret security clearance which the job actually called for, but had been denied because I had a police record, and that would require another waiver which they'd be just so happy to obtain. Promise.

They even offered to get that teenage record expunged if Id just be a team player and re-up. And by the way how the hell had that not been taken care of already anyway, they yelped indignantly?! And why didn't I just re-up anyway . . .

Well I didn't. I took the short-timer company clerk Harry H, a quart of whiskey and he cut some orders to get me transferred to Fort Campbell. Harry was just an E4, having been busted once for some previous sin, but he ran the company and had no trouble slipping those orders past the company commander along with the morning report. Not the first thing the Captain had overlooked.

Everybody also overlooked the fact that although Harry was an RA (regular army) he was short, and they might have been on the lookout for a stunt like that because he was smart and getting sassier all the time. But they weren't and he cleared post a couple weeks after I did, with his discharge.

I was already gone, out of sight, orders in hand. But not dumb enough to go over the hill. I reported to Fort Campbell just like my orders said. The Fort Campbell post office is in Kentucky alright, but just barely. It's the home of the 101st Airborne Division, the Screaming Eagles, but most of the reservation is in Tennessee in fact, and not particularly close to Louisville.

But I was still in the army, which had straightened me out some I guess I gotta admit, and I was still on jump status, loaded for bear.

And Chattahoochee is still 500 miles from Miami, where I grew up, and my father is long gone, but that's another story, for another time.

DISCLAIMER

The events in this yarn really happened, as told here. I was there. I wasn't one of the six who threw Johnson down the stairs, but I was one of the 30 who never said anything about it. Just like the whole fucking army never said anything about it. Some of us didn't really go along with the blanket party idea, but about half did, were in favor of it. As far as I know none of the rest of us ever even considered interfering with the plan. Those guys weren't to be denied.

The funny thing was, a year earlier . . . more like a year and a half . . . I was "sitting in" at dime-store lunch counters in Lexington with about a dozen young white people, mostly college students, and about the same number of black would-be radicals, protesting discrimination in the early days, locally, of "the movement.

I was an indifferent student protesting the venality, the smallness all around and so suitably susceptible to "the cause." But that was a non-violent movement preaching peace and I didn't really fit in, and when the fat, pig-eyed cracker bitch working the counter dumped a tureen of hot soup into the lap of the black "chick" occupying the stool next to me, I started over the counter to strangle her and had to be pulled off --- and dressed down --- by members of the group and that pretty much ended my days in "the movement."

A girl I was going with at the time claimed she was pregnant and I dropped out of school and got a part-time job in a supermarket to prepare for "having to get married." I was out of money anyway, having to forge my father's signature on a 600-dollar national defense loan application to pay my tuition, etc. She said she had a miscarriage so we didn't get married after all but the college notified the draft board I'd dropped out and I did indeed get drafted.

After two years of active duty and two years of active reserve duty, I was still attached to the army by law, but back home working civilian construction jobs and learning to be a surveyor, which didn't pay much better but was a notch above the moronic laborers working construction whose aim in life was to spend all their pay getting drunk in strip-club bars and trying to fuck each others' wives.

They were typical of the crowds assaulting the marchers bent on getting an open housing ordinance passed by the city of Louisville, three year after I'd gotten off active duty. The demonstrators were led by a local pastor, Rev. A. D. Williams King, younger brother of Martin Lither King Jr.

Busy working full-time and trying to finish up college full-time on the G.I. Bill, I wasn't paying much attention to the open housing cause, but when the marches started, and especially when "martin luther coon" came to town to march, the city took real notice. I spent a fair amount of time arguing about it with the young crowd, mostly in bars, and particularly with several of my in-laws, who seemed unaccountably fearful of niggers moving next door to them, but that was pretty much the end of my formal "nigger-loving" days.

The ordinance got passed and the brief violence it engendered was long-forgotten by the time "forced busing" rolled around seven years later and surprised "community leaders" with the violent resistance it brought about. School integration had gone remarkably smoothly at the start of my senior year in high school in "56, and the busing uproar 20 years later caught those "community leaders" way off guard.

But busing was accomplished, whatever that meant. Among other things as it turns out, it accomplished the resignation of the rank-and-file population to the fact that it wasn't ever going to be represented by its "leaders," an elite who managed to enact laws certainly not representative of that population's voice.

NAKED MAN COMES TO THE DOOR

I flew into Memphis on a non-stop connection from Denver, direct from the mile high Rockies back down to the land that time forgot.

Jeff picked me up at the airport and we adjourned to the lobby of the Peabody Hotel downtown. A singularly civilized place where we could relax and get our bearings before sliding on down into the Delta, somewhere out there in the Mississippi darkness.

That was the plan anyway. The damn ducks were back in their rooftop nests for the night, the tourists were thinning out and we settled back in our easy chairs listening to the piano man, to work on the plan.

Plan? The waitress came around to ask about our drinks and right then the "plan" got all shot to hell. I don't remember whether she pointed it out or it was Jeff's own idea, but he immediately spied the strawberry drink machine gleaming there off to the side in its own special weekend spot, and there was no turning back.

Instead of our usual sensible scotch and waters, he became fascinated, transfixed, with the thing, dispensing this rose-colored slush like pink smoothies, frozen daiquiris the waitress said, but I don't think Jeff was even listening by then. He was already slurping.

And slurping. I tried one of the damn things --- they were refreshing --- but he was already hooked on the melted mush oozing out of that silver machine. It reminded me of one of those old one-armed bandits you'd see once in awhile in a roadhouse when people used to go out for a drive. He was hooked and I thought for a minute we were gonna have to dynamite the place to get him out of there.

And that would have been a shame. Everybody knows the Mississippi Delta begins on the front steps of the Peabody and winds up on the docks in Vicksburg. The Peabody is the Plaza, a thousand miles removed, the last bastion of civilization atop strange Mississippi, the perfect place to launch any excursion into the Delta. We were definitely on a mission and it was high time we got going.

We left the grand comforts of the hotel and set out for Cleveland.

Cleveland Mississippi, in the heart of the Mississippi Delta, home of the Delta State University Statesmen --- also known as the Fighting Okra --- and where Jeff's girlfriend, Marion, was a senior, majoring in English.

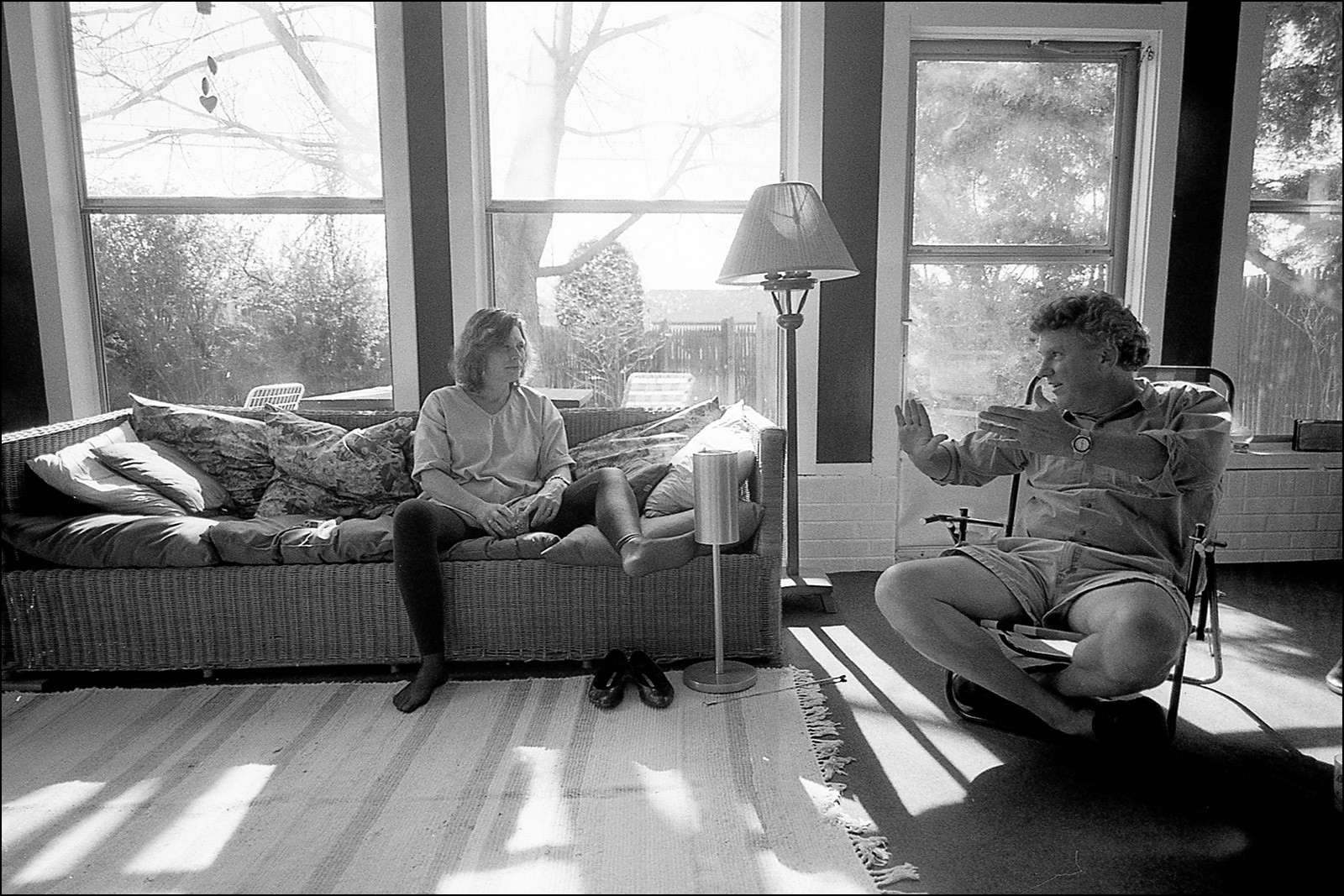

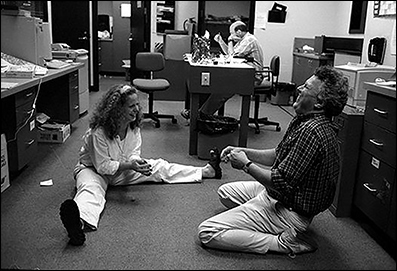

Jeff and Marion shared a small house in the small town on a street that had been paved at one time, long enough ago that half of it was now chunks of blacktop and the rest broken down to the big rock aggregate sub-grade underneath, bumpy and a little hard on tires. Jeff was winding up his Guggenheim project and Marion was finishing up her B.A.

We fired up some medicine and Jeff took the wheel of his compact little Subaru and pointed us south down Third Street, out of Memphis to where it turns into Highway 61. Revisited. Oh yeah, for sure. We made a quick stop at a liquor store 'cause we knew we were gonna need more medicine eventually, more fuel to power us through that thick, mostly dry county and damp Mississippi darkness, and on to Cleveland a hundred and twenty miles away. Oh yeah.

We hit town, scooped up Marion and drove across state 50 miles to Greenwood to meet up with my girlfriend Mary Stuart and her pal Lisa. Lisa was the daughter of old Delta money where white people own everything and black people do all the work.

Lisa had arranged for us to rendezvous at Lusco's restaurant, a Delta landmark in the Lusco family for a hundred years, known for good food and specializing in steaks, seafood and game. It has a half-dozen private dining rooms each curtained off for privacy, and plenty of wine and beer and ice and mixers. The place to meet in Greenwood.

Everybody was hungry and we ordered everything on the bill of fare, sloshing it all down with various mixtures of Scotch wine, bourbon and lemonade. The food was as good as expected but in no time at all Jeff heaved his back up along with most of the stomach sins he'd accrued all day long.

Somehow he managed to push away from the table just in time and aim downward. Even more miraculously everybody else was able to lurch clear and avoid most of the splatter. Lisa quickly took command and commandeered one of the porters to swamp it all up into a bucket and mop the floor down with Lysol.

The old gentleman took care of the nasty business with dispatch, indicating he'd had plenty of life experience with such unpleasant duty. I didn't actually see it, but I'm sure Lisa crossed his palm with an appropriate amount of greenbacks, maintaining another fine old Delta tradition with equal dispatch and the practiced aplomb of gentry.

We paid the bill and stumbled outside, Jeff stumbling a little extra although I was trying to help him along, and stuffed him into the back of Lisa's bigass Buick. Mary Stuart volunteered to keep Marion company in her modest old Mazda four door on the long drive back to Cleveland, another one of her typically fine and welcome noblesse oblige moments.

Marion was mortified --- and greatly annoyed --- by Jeff's ridiculous behavior. She was also in something of a state of shock. She'd never met any of us except Jeff. We all knew each other from our working days in Jackson and we all knew any of us was quite capable of some pretty ridiculous behavior most any time. Hell, it was expected.

All Lisa and I had to contend with was the occasional pathetic moan emanating from the back seat, which struck us as hilarious every time. It was past midnight by the time we got back, but the night was far from over even if we didn't suspect so at the time.

Marion and Mary Stuart got there first and I guess Marion had forgotten she'd left Angus cooped up in the house for three hours while she was gone 'cause as soon as they opened the door he jumped on them paws first and knocked them both down. He was happy to see them.

Angus was a Great Dane, big as a pony, that Marion had rescued from the dog pound where she worked part-time because his number was almost up there. He ate like a horse, or at least a pony, and worked up an appetite by running back and forth the length of the yard all day. Jeff and Marion had attached a long chain leash to the clothesline overhead and the huge dog could get rid of a lot of energy and overgrown puppy enthusiasm in that long yard.

By the time they got him calmed down a little Lisa and I and what was left of Jeff came in and Angus got to welcome us all again, sheer joy, boundless enthusiasm bounding all over the kitchen and jumping on us while wagging his little bobbed tail furiously. He was a happy dog.

We hooked Angus up to his leash and took turns using the bathroom. Marion had salvaged Jeff's untouched steak, like a starving college student, and the debate about its fate began. Jeff was clearly in no shape to eat it. He was sprawled on the couch in the living room, taking up most of it, removed from it all. Best to let sleeping dogs lie anyway.

Marion of course was sensibly in favor of sticking it in the fridge for tomorrow, but then Lisa came up with the winning solution. Angus. The rest of us were enthusiastically in favor of that idea of course. Except for Jeff, who even managed to limp into the kitchen briefly to defend his steak rights, but the rest of us quickly hooted him down. And I don't think I've ever seen anything sadder than the look on his face, and it was kind of a sad face at that back then. In fact, the Fool always told him he could make a fortune renting it out at funerals.

But imagine Angus's pure unalloyed joy when he realized he was being given the gift of a two-in-the-morning, twenty-five dollar T-bone, all to himself. He jumped straight up in the air and then wolfed it. Jeff had gone back to the couch, unable to watch.

We were all milling around in the kitchen in the back of the house, trying not to think about the 150-mile drive to Jackson, when somebody noticed there was somebody at the front door. Marion went to answer it and we all followed so we could all see at once that it was a skinny old man. And we all could also see at once that he was nekkid as a jaybird.

We were all pretty stunned naturally, then Lisa stepped out on the porch and demanded to know who the hell he was and what the hell he was doing here. He couldn't make any sense, drunk or something, and shivering to beat the ban in the night chill. Lisa said somebody should get him a towel or something but it was Marion who had the presence of mind to bring him a blanket and wrap him in it and bring him on up into the house.

Hell, he didn't seem dangerous, he was old, in his 60s at least, skinny as a rail, and he damn sure wasn't hiding any weapons anywhere. He was obviously out of his mind, probably drunk, probably mindless from being drunk for 50 years. And he was naked and alone, nameless on a chilly night in a small town in the Mississippi Delta, in the dark, in middle of nowhere.

I got a chair from the kitchen and put it next to the "furnace" which was really a 3x4 brown stove, an overgrown space heater in the living room which supplied the house with a very modest amount of heat.

We all fell on him at once, machine gunning questions at him like cops in one of those old black and white movies on tv. He was bewildered of course, more or less totally uncomprehending. We never did even get his name out of him but we did manage to find our what happened to his clothes.

A bunch of hooligans in the Chat and Chew two blocks down the street had taken them and to be extra mean had thrown them up on the roof of the appliance store across the street. The Chat and Chew was a house, about twice as big as the one Jeff and Marion lived in, with a makeshift bar, a loud jukebox and a couple of big beer boxes in it. The kind of place nobody in their right mind would go into on a Saturday night.

Our man was calm and cool but a lot warmer wrapped up in his blanket by the stove than he'd been out on the porch. There were two or three houses and some weedy vacant lots between us and the Chat and Chew and he'd probably chosen our house because there were still lights on. Lisa had gone back out on the porch to check for any leftover hooligans but there was no sign of any.

Marion always claimed our man still had on one green sock but you couldn't prove it by me. But it was dawning on us that we needed to figure out what we were gonna do with him. Marion called the cops and a deputy arrived about half an hour later. He wasn't surprised to see him and wasn't surprised that he'd run afoul of the Chat and Chew. Another Saturday night.

The deputy called him "Jimmy" and said he'd take care of him. "Jimmy" was always running afoul of something or other apparently, a defenseless halfwit loose in a cruel world. The deputy said he'd bring the blanket back but I'm not sure he ever did.

We were all dog-tired and it was time to crash. It was Sunday morning now and Mary Stuart, Lisa and I needed to head out for Jackson. We caught a break by being able to stop off at the "lake house," which actually was a cottage Lisa's family owned on a marshy lot overlooking a back channel of the river in Greenville, 30 miles down the road.

We all slept till noon, waking up grumpy and hungry, counting on Lisa to know of someplace we could get some breakfast on a Sunday morning in the wilderness, and she did. Turned out to be some black people's house which doubled as a family-style "restaurant" which you'd run across every once in awhile in Mississippi.

Lisa had been there before. By the time we got some coffee and grub in us our dispositions were improving markedly to the point where we were laughing our heads off recalling the night before. Whenever any of us remember that night, often and always fondly, never to be forgotten of course. 33 years later still always referred to as the night the naked man came to the door.

The next morning in Jackson I drove Mary Stuart to work in her car and then to the newspaper where Jeff and I used to work and took out a classified ad to compose my marriage proposal, the main reason for my trip. A few months later we hired a preacher and got married, on Derby Day, in the seal fountain in the Denver Zoo. Jeff latched onto what turned out to be a 30-year job with the paper in Memphis and he and Marion got married shortly thereafter in the courthouse downtown there in Blues City.

BACK TO TOP

DEEP THOUGHTS

PARAPHRASING HISTORIANSThe 20th century ushered in a shift from a culture of character, which emphasized the importance of our private behavior, to one of personality in which the exalted social role was that of a performer.

And author Steve Almond: . . . but aren't nearly all of us footnotes in the end? Don't the dreams we arbor eventually give way to the actuality of our lives? Our most profound acts of virtue and vice, of heroism and villainy will be known by only those closest to us and forgotten soon enough. Even our deepest feelings will, for the most part, lay concealed within the vault of our hearts. Much of the reason we construct garish fantasies of fame is to distract ourselves from these painful truths. We confess so much to so many, as if by these disclosures we might escape the terror of confronting our inner selves.

Or in the words of the Bard: "This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong/ to love that well which thou must leave ere long."

THE BASKETBALL MANIFESTO

It occurs to me that basketball ---- big-time college and professional basketball, as seen on tv, is an excellent example of our national paradigm. There are others, but all stem from the root of democracy. And if may paraphrase Dr. Freud, democracy and its discontents.

Democracy contains its own corruptive, suicidal killer because by definition it must turn on the lowest common denominator, and so turning, so constructed, carries the seed of its own destruction. Built-in as it were.

Nothing built on the premise that its least-accomplished members can sustain it, let alone make it prevail, can possibly endure. Not Marxism, not "democracy." Have we learned nothing from Darwin?

"Aha," you say (accuse), "Social Darwinism!" Well yes, if you remove the loaded adjective "social." That instead makes it objective, scientific if you will; man's only great, human discovery.

This nation supposedly was founded on the principle of enlightened self-interest, an oxymoron if ever there was one. Self-interest and democracy? At the same time? You must be kidding.

So let's call a spade a spade. This nation, this culture, is not --- and never was --- a democracy. At best a Republican accommodation, both in the original sense of the word and now in what that word has come to mean. And I do mean mean.

But that doesn't prevent our mulish insistence that we are a democracy, despite all evidence to the contrary, and that everybody else in the world should be just like us. Imagine the arrogance, the conceit. Especially since it's based on our own abysmal, bottomless ignorance.

That ignorance is manifested, graphically, every day in our popular culture. The ignorance of denial, the denial of what we see plainly before us, all around us. The sad denial that confuses cause and effect. And nowhere is it shown to us more plainly than in basketball, big-time college and professional.

Televised basketball. With its slow-motion, multi-camera, instant replay techniques. We see clearly that that player pushed/shoved/held/hooked/hacked that other player. We see clearly that that player palmed the ball, a clear violation of the rules; and that most players do it most of the time; that that player took more steps than are allowed without dribbling, a clear violation; that that player interfered with the ball while it was still in the basket, or might be, a clear violation; and on and on.

We see these things, we can't help but see them, from every possible angle, they're replayed incessantly. We see clearly that this game is not being played according to the rules. Not even close. We see it, but we choose not to see it. We choose to ignore it. I wonder why.

I wonder why we don't choose another game, a different game. Or better still, I wonder why we just don't insist that this game be played correctly, according to its rules and regulations. It's a good game, basketball.

Or is that like asking why American business should be conducted according to its rules and regulations? Or asking businessmen, all of us, to be ethical, even our congressmen, our city councils, our state legislators, our priests? To be honest. Or is that being "hopelessly naïve'? An ever-more popular phrase as our "democracy" rolls on. Why did it become so popular?

Well then who are we? That even our entertainments, our games are dishonest, That we are dishonest, even with ourselves. So self-deluded as to be powerless, unlike the man in the Viagra commercial who easily escapes the trap of the muddy road because he knows what he's made of. But of just what is he made?

Is this the same man who needs the assistance of a pill to become aroused in the presence of his wife? Just how manly is that? And how womanly is she who doesn't arouse her man unless he's assisted by a pill? Does she care? Feel demeaned? Aroused? Or does she just reflexively excuse the un-naturalness of things along with the dozens of other thing she excuses every day? Did she not see, with her own eyes that guy palm the ball?

Have we lost the ability to indeed see? To see what is before us, in plain view? Can we no longer distinguish what is fact and what is fiction? Shadow and substance, illusion and reality? Our self and ourselves? How else to explain our obeisance to what is not ?

Or did we just give up? Does it all just come down to the line of least resistance? Was the mongrelization of our culture, our "democracy," inevitable? Is hip-hop, rap, the equivalent of an Ellington etude? A Gershwin rhapsody? Is the tuneless. non-melodic chanting of rhymes as accomplished as those in nursery school, by the least educated and accomplished strata of society, the same? Is that why it's so pervasive?

Or did we just give up? Get bulldozed, browbeaten by poorer, hungrier citizens? Jettison all standards of taste, artistry, accomplishment? Abrogate centuries of real effort and accomplishment just because it was easier to give in? Have we just become so used to being told shit is apple butter that we're defenseless, can no longer tell the difference? Or is it just too much trouble? Is everything indeed, "all good?" Does everything taste just like chicken? Chicken fingers? Are we at last a democracy?

A BITTER COLD STORY

I've never been colder than a morning in Oklahoma just over the Colorado line. And you didn't even know Colorado and Oklahoma have a border, but they do, a 50-mile strip atop the panhandle, squeezed in between Kansas and New Mexico. And one January day back in '88 I crouched down in a windswept field in the middle of nowhere and shot pictures of a very old Indian man bundling up broomcorn, used in making household brooms by hand, a pioneer tradition in Oklahoma.

There were patches of snow dusting the ground where the wind hadn't blown it away yet, somewhere on those Oklahoma plains 25 miles from Texas. The old man sat on the cold ground with his back to the wind, gathering the foot-long sheaves barehanded, stoic, uncommunicative. You'd have thought he was dead except for the monotonous, rhythmic working of his hands, kind of like some small worn-out farm machine.

His eyes were dead though, emptied out of a life gone by, already over except for the shouting, as they say. But there'd be no more shouting for this old man, just how old it was impossible to say. The wind was relentless, merciless, watering my eyes enough so that focusing the camera was dicey at best. I laid there on that cold ground as long as I could, snapping a few frames, guilty, for stealing the old man's soul, guilty knowing I'd be back in the nice warm car in a matter of minutes.

Joe had stayed in the car the whole time, engine running, heater on. He'd write the story, putting a light glaze on a dull catalog of numbers and other uninteresting facts, a story he could have written in the office; he already had all the information. A story already tired, another yarn about a dying industry that had already outlived its folkloric pension. Everybody already knew nobody needed hand-made brooms, made out of broomcorn or anything else.

In truth we'd driven all the way down from Denver for a photograph of an old man sitting out in a field in the bitter cold going through the useless motions of a time gone by. But we didn't do his story, the story of the end of a way of life for a couple dozen Chickasaws. That story, that bitter story, had already been done, more or less, dozens of times before. A story as bitter as that cold day in the panhandle, bitter as our mission.

GRACELAND

Right off the bat the dictionary provides a couple-dozen definitions of the word, grace. First and foremost, it's a noun, a thing. A little farther down it turns out it also can be a transitive verb, or an adjective, or even an adverb. And in truth, given the wholesale abandonment of any rules of grammar these days, grace, like any of our words, can be used any which way, anything is permissible, anything goes, as duly noted, once and for all, by the late Cole Porter.

It's a short prayer, usually seeking a blessing, a benediction. And it's a state, a state of grace, a state of being in good favor, a state of good times. It's thanks; it's praise; and poise; beauty and charm; a title of respect. It's elegance, harmony and style, balance and finesse; it's plaintive, yearning; it's romance . . . a wistful romance. And god help us all, we hope it's mercy.

It's 13.8 acres, nine miles south of downtown Memphis, four miles north of the Mississippi state line. The daughter of a Memphis businessman inherited this portion of a small farm on the outskirts of the city and built a colonial-style mansion on it in 1939. Elvis Presley bought the property in 1957 for himself and his family; 20 years later he died there on a hot August night, and every day since, thousands pay to tour the place.

Inside, the house is a mess, a hymn to wretched excess, a garish paean to bad taste. To call it tacky would be charitable. Arranged and decorated by the new owner, a sudden millionaire, an earnest country boy with a guitar, a turned-up collar and a load of rose oil and Vaseline in his hair, four years out of high school, four years removed from driving a truck around the city for minimum wage. But it only took a couple of those years to change the world, and pile up more money than he knew what to do with.

Outside, the grounds are still pretty, still serene in the early morning light, the chest-high stone wall running along front somehow separating the place from the four lanes of small, spotty commercial ventures strung along US 51, South Bellevue Boulevard; Elvis Presley Boulevard since 1971.

From 7:30 to 8:30 every morning visitors are admitted to the grounds for free, but not to the house; that costs a pretty fair chunk of change. But if you're traveling a ways to visit Graceland, you might as well go the whole route and go on in.

But the real point of going to Graceland of course is not to gawk at bad interior decorating anyway. The real point can be understood only by frequent, close listening to the song by Paul Simon, "Graceland," released 25 years ago this coming August. Close, attentive listening, or the song can't be understood, and the reasons for going to Graceland will be lost.

Those reasons can't be precisely articulated. They literally cannot be articulated literally. They can be expressed, voiced, only in the song. And then only felt, felt in the first person. The lyrics really can't define those reasons either, freely admitted by the author, within the song itself: " . . . for reasons I can't explain there's some part of me that wants to see Graceland . . . " Those reasons are amorphous, the ghosts in our blood who seeped in there when we weren't even looking, and made us who we are, who we became.

Reasons that can't be explained, only felt; felt in the sound of the song, the feel of it, in the words and music, its very construction, the architecture of the song, our apostles' creed captured in the arrangement, the modern studio production of the instrumentation, the layering of sound, the wistful, wishful words . . . not explained, but true.

That recurring, propulsive beat, the open, wind-blown chorus in the back, those illusory lyrics; a perfect capstone, the perfect epitaph, for our rock and roll century, the 20th, the last American century.